|

|

Part II By Walter Rice Ph.D. and Emiliano Echeverria |

Market Street, San Francisco’s main stem, was laid out in characteristic San Francisco fashion – without regard to topography. Jasper O’Farrell, an Irish engineer who had migrated from Valparaiso, Chile, began surveying and mapping the city’s streets in 1846. Based on Philadelphia’s grid system, O’Farrell expanded the street system in all directions from Portsmouth Square, then the city center. Underwater "paper blocks" were created, since some of O’Farrell’s streets went straight into San Francisco Bay! Others have grades of more than 20 per cent, and some grades too steep for any type of street vehicle.

O’Farrell also laid out a second grid south of the first. The new grid was rotated counterclockwise 38 degrees from the first. Market Street, as O’Farrell designed, separated the two grids. It was to run from the bay to Mission Dolores – where in 1776 San Francisco got its start.

Market Street of the late 1850s was far from being either broad (except on paper), magnificent or populated. Sand dunes obstructing the street towered as high as 60 feet above "street level." Stagnant pools of water occupied sites destined for commercial development. The wind literally propelled real estate, consisting largely of sand, in all directions. On wet days Market Street was muddy. On dry days it was dusty. Many regarded it as too wide. Indeed, O’Farrell himself briefly left San Francisco to avoid the repercussions from those who thought the width of Market was not practicable.

No one surveying Market Street of the 1850s would have dared to dream, that within a generation, street railways would operate cars less than every fifteen seconds. Although San Francisco’s population and commercial activity was centered to the north of Market Street, nevertheless there was an entrepreneurial sprit to create a street railway for Market Street.

The explanation was land. The goal was to bring the land to market. The method would be a railway. Thomas Hayes, who owned a large tract in the Western Addition, now known as the "Hayes Valley" and the banking house of Pioche and Bayerque, who held Hayes’s mortgage, ultimately joined with several large property owners in the Mission, to form a business alliance to build a rail line connecting the main part of San Francisco with the old Mission settlement, a distance of three miles.

Small time omnibus operators characterized San Francisco’s transportation scene in the 1850's. Omnibuses were rough riding eighteen passenger urban stage coaches. Two or four horse teams drew them.

The City’s pioneering transit line began, in June 1851, as a half-hourly omnibus route from Portsmouth Square to Mission Dolores using Mission Street – one block south of Market Street. Fares initially were 50 cents on weekdays and $1.00 on Sundays. Competition soon forced the fare down to 10 cents.

However, to

Hayes and associates the omnibus was an unsatisfactory solution. The city

was outgrowing them. They would build a horse car line. By

operating on rails, horse cars avoided (in theory) the problems of

ungraded streets. Importantly, horse cars had superior

productivity since they enjoyed reduced friction compared with

omnibuses. This allowed companies to increase the number of paying

passengers.

|

San Francisco Market Street

Railroad |

|

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved the franchise on June 19, 1856. This was the era of the Vigilantes, and unstable government. Civil authority was in serious disarray. The state of California reacted by passing the Consolidation Act of 1856. San Mateo county was severed from San Francisco. Some of the city’s authority was transferred to the State Legislature. When this happened, the franchise died.

Immediately, Hayes and his associates reapplied to the State Legislature, and a new franchise was granted on April 6, 1857. Thus began California’s second passenger railroad – the San Francisco Market Street Railroad. The railroad was also known as the "San Francisco & Mission Rail Road," until reorganized in 1859.

It took, however, until after the reorganization for Pioche & Bayerque to provide adequate capital to start construction. The relationship the railroad and its banker was close. Company offices were in Pioche & Bayerque’s building at Montgomery and Jackson streets. (This building was not demolished until 1964.)

On May 3, 1859, grading began southwesterly along Market Street, beginning at 3rd Street. Grading was not as easy, as it would now appear. High sand hills often covered Market Street’s official grade. Scrub oak was laid as a thatch to help prevent sand engulfing the rails. A steam locomotive, built by Young and Stoddart, began moving, on December 28, 1859, cars loaded with sand from 3rd Street to lower Market Street. This date marked the beginning of the steam locomotive era for San Francisco.

During the construction period, the downtown streets next to Market Street were lowered, including the surrounding blocks. Once these projects were completed the "downtown" gained the level topography that it has today.

The roadbed was completed one month later, in late April, thanks largely to the use of a steam shovel (steam paddy). From 3rd and Market the line ran on Market to Valencia and then on Valencia to 16th Street.

The company contracted with John W. Shaw for the track work. Shaw later had a long and distinguished career in railroads, until his passing in 1898. An associate of his, Frank McCoppin, became the superintendent of the new railroad. McCoppin would become a major figure in San Francisco.

Track laying began on April 2, 1860, again at 3rd and Market Streets and lasted until June 28. The railroad’s yards & shops were on the west side of Valencia Street, north of 16th Street. The route was single track with turnouts, laid at 5’6" gauge. There were no turntables. Trains ran forward in one direction and backwards in the other.

On the 2nd of July of that year a car was placed on the tracks in an unsuccessful attempt to use horse power. Originally intended as a horsecar or mule car line, the railroad had planned for steam power in the event the grades would be unsuited for animal power. This was the case. Charles W. Stevens, the railroad’s master mechanic, wrote, in 1861, the line had "grades of upward of sixty feet to the mile."

The company laid T-rail of the type then used for steam operation. However, instead of using rail joints to connect the rails together, the ends of rails were merely spiked to a tie. This construction resulted in uneven track and was a factor in some of the constant criticisms of the line – namely, a rough ride and frequent derailments. Passengers were annoyed. Importantly, when competitive horsecars lines were built, many of the Market line’s riders deserted to escape these inconveniences.

A steam car designed by Spratt and Dibre and assembled by the Albion Foundry on Pine Street was available for the inception of service. Steam cars were part passenger and/ or baggage car and part locomotive. Steam dummies, used later by other San Francisco companies (see, Part I (All Aboard to the Water "Playgrounds" of San Francisco)) had their locomotive bodies camouflaged by a wooden car body designed to resemble that of a horse drawn streetcar. The idea was to stop horses from being frightened by a belching steam locomotive. The camouflage did not fool horses.

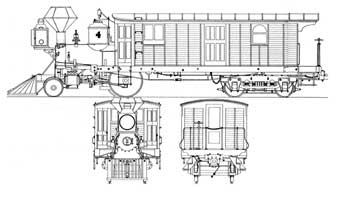

Steam car No.1 was twenty-four feet long. Six feet was required for the engine, five feet for the baggage area and remaining thirteen feet was space for twenty passengers. Its car body rested on upon four thirty-four-inch wheels, two of which were drivers. Power was directly applied from two fourteen-inch stroke six inch vertical cylinders. An upright tubular boiler, built by the Thomas Snow Foundry on Market Street, was placed directly above the driving wheels. No. 1 weighed seven and half tons. Another San Francisco firm, Kimball & Baton, constructed the steam car’s wooden body.

No. 2 completed by Albion in the fall of 1860 and No. 3 built the next year were only eighteen feet in length. The engine used eight feet with remaining ten feet for a baggage compartment. Axles were eight feet apart, with all four wheels connected. No. 2 and the line’s subsequent steam cars had horizontal boilers. The last locomotive, No. 4, was also built in 1861. The twenty-four foot No. 4 had a single pair of thirty-six inch drivers and like Nos. 2 and 3 had only a baggage compartment. All three engines processed nine by fourteen inch cylinders. No. 4 had a return tubular boiler.

San Francisco firms of Kimball and Company and Casebolt & Kerr built fourteen passenger cars. These cars were designed to be pulled either by a team of horses or by steam power. Numbered 1 through 14, they were forty foot long cars with a seating capacity for sixty-four. Some cars, those built by Casebolt & Kerr in 1860, offered rooftop open air seating. In the car’s center was a staircase leading to the roof.

Management was

not concerned that their franchise called for animal power. They

received permission to substitute steam power, in May of 1861, eight

months after they started regular steam train service.

However, there was an important proviso to the amended franchise –

namely, all steam power would be off Market Street by

1866 (later extended to March 1867).

A Memorable Opening

The troubled republic was eighty-four years old on July 4, 1860 when by invitation of the Market Street Railroad’s Board of Directors, a group of fortunate San Franciscans rode the inaugural trip of reputably America’s first steam-powered street railway. Steam car No. 1 had the honors. Despite the fact the inaugural trip was subject to countless delays causing some riders to return to the city by omnibus, it was nevertheless regarded as a successful experiment. In fact, the populace hailed it "as one of the greatest miracles of western advancement." Newspapers dutifully reported the occasion as a harbinger of great things to come for San Francisco. Before regular service could begin, however, both steam car and coaches had to be modified. No. 1went to the Albion’s shops to get new and lower gears.

Revenue service began on July 15, 1860, with the issuance of the first timetable. The initial schedule called for hourly service between 8:00 A.M. and 8:00 P.M.. Trains destined for the Mission departed from the depot at 3rd & Market Streets on the hour, and returned from the Mission depot on the half-hour. Twelve round-trip trains ran successfully on the first day. One-way travel time was a rapid 10 minutes.

By September

25, the line could boast a full schedule, with trains until

12:30 A.M. Given the obvious superiority of steam power for this

route, on October 9, 1860 the San Francisco Board of Supervisors

voted to table the motion compelling the company to use horses, and

urged the State to modify the franchise accordingly. Contemporary

newspaper accounts spoke of hourly service, with full

loads most of the day, and on Sundays passengers often filled

the cars beyond capacity. In two months short time, property

values in the Mission increased significantly. By October 15, the

tracks on Market Street below 3rd Street were ready, and importantly

the company overcame the legal obstacles to using steam on lower Market

Street. Afterwards the line’s eastern terminal for all trips

was California and Market Streets (close to today’s Ferry Building).

To The "Willows" and Hayes Valley

To bolster traffic, the owners of the Market Street Railroad explored a variety of options that would complement their railroad investment. A solution was found in a modestly successful resort called the "Willows" that featured a then famous suburban garden. On September 1, 1860, the railroad’s banker F.L.A. Pioche announced he had purchased the "Willows." Pioche further revealed plans to extend the Market Street Railroad directly to the gates of the "Willows." By January 16, 1861, all was ready. After that all Market Street trains ended at the "Willows" depot. The depot was located on Valencia between 18th and 19th Streets. Positive results were immediate for both railroad and the resort.

Thomas Hayes

had originally projected the railroad also to serve the area of San

Francisco that bears his name today – the Hayes Valley. Hayes was

the major property owner in the valley. The "gandy dancers" had hardly

finished the line to the Mission, when they were called upon to

construct a branch line from Hayes and Market Streets into Hayes

Valley. The terminal would be at the site of the then

under construction "Hayes Pavilion" at Hayes Park, Laguna and Grove

Streets. (Often maps show incorrectly this line ending at Hayes and

Laguna, but contemporary newspaper accounts verify the routing to

Grove Street.) On October 15, 1860, the Hayes Valley branch opened.

Regular service ran from Market Street, where it connected with main line

trains, to Laguna and Grove with occasional special service from

California and Market Streets. Steam powered service was

limited. It ran only on Sundays, holidays, and special

occasions when pavilion traffic warranted. This

service ran from 12:30 P.M. until 11:30 P.M. At other times a

one-horse shuttle car served the branch. The branch was a financial

disaster, since the population of the Hayes Valley in 1860 was a mere

five.

Competition and Insolvency

Market Street steam train service did not signal the end of the omnibus era. New omnibus operations soon began – some lines complemented the railroad, whereas others were competitors taking away riders. On March, 3, 1861, the omnibus operator, George H. Finch started an omnibus service from Hayes Park to the newly opened cemeteries near Lone Mountain. On March, 10, 1861, the firm of John Gardner, Michael Skelly & Co. opened an opposition omnibus line from Portsmouth Square via Hayes Park to the cemeteries. Richard Dougherty opened still another omnibus service from Hayes Park to the Cemeteries on March 25. These operations were generally helpful. Passengers would take the railroad to Hayes Park where they transferred to an omnibus to complete their journey to the cemeteries. The combination train-omnibus trip was materially faster than an omnibus only trip.

By the spring of 1861, the railroad was enjoying the record level of attendance at the "Willows" and Hayes Park. This prosperity was to be short-lived. The Market Street line proved the superiority of rail for moving large groups of people, sometimes as many as 10,000. The Hayes Pavilion and "The Willows" had become San Francisco's first large "Sunday Amusement" transit destinations. Many similar venues would be developed and promoted.

April 29, 1861 would prove to be a day of major significance for the Market Street Railroad. On that date ground was broken for the San Francisco & San Jose Railroad (SF & SJ). In the future, the two companies would have a very close relationship, despite the fact that initially no physical connection was then planned between the two railroads. The SF & SJ completed its line from San Francisco to San Jose in January 1864.

San Francisco street transportation was about to become highly competitive. On January 22, 1861, the state legislature was petitioned by no less than three separate companies for horsecar franchises. After "much agitation" from San Francisco business interests and the petitioners, the legislature in early April began hearings. On April 17, 1861, the legislature authorized the franchises for the Freight (or Battery Street) Railroad, the Folsom Street Railroad, and the Omnibus Railroad.

Although many subsequent lines of these companies were not in direct competition with the Market Street steam line, others were and did lure traffic away. Both the North Beach & Mission (the Folsom Street Railroad and the Freight Railroad were consolidated, August 24, 1862) and the Omnibus built lines designed divert traffic away from the Market Street Railroad. The Omnibus opened a line January 11, 1863 on Howard Street (two blocks south of Market Street) to Center (now 16th) Street, then up Center to Dolores in direct competition with the Market Street Railroad. During the summer of 1864, the Omnibus built a branch line on 18th Street from Folsom, to the Willows gate at 18th & Mission Streets. This branch, which opened during the fall of that year, siphoned off yet more passengers from the Market Street road.

When compared with the steam line, horsecar companies built these new horsecar lines with both lighter construction standards and rolling stock. The horsecar lines ran, with few exceptions, on streets that the city had previously graded to the official grades. In short, their capital investment was much lower. Smaller crews were needed for the horsecar operation too. These factors enabled the horsecar operators to provide more frequent service. Wisely for revenue generating purposes, the horsecars ran along built up streets. Market Street, in contrast, was still largely undeveloped west of 9th Street.

A third horsecar company, the Central Railroad, began construction in mid-1863. One of its lines was the first direct rail route through the Western Addition to the cemeteries at Lone Mountain. The Central’s line compared to using the Market’s Hayes Valley branch was not only quicker, avoided a transfer, but was also cheaper at ten cents, and less roundabout. More traffic was lost.

To compound matters, at the beginning of 1864, a full-fledged fare war broke out between the horsecar companies. The North Beach & Mission first lowered fares, but the Omnibus soon joined to maintain revenue and market share. By March, according to city hall, the competitive struggle had reached ruinous levels. The City now stepped in to regulate fares. However, the horsecar companies went to court to block fare regulation. On March 23, 1864, the court decided in favor of the City. The street railways had lost. They now needed municipal regulatory approval to alter fares.

The combination

of high fixed and operating costs, compared with the competition, coupled

with declining revenues resulted in the Market Street Railroad not

earning expenses. Interest payments to the bondholders were

impossible. The two bankers, Pioche and Bayerque were forced

to accept positions on the railroad’s Board of Directors, in

lieu of loan repayment.

The Last Whistle

The financial picture was getting steadily worse. To offset losses management on April 1, 1864 lengthened headways to every forty minutes from half-hour service. This only made the competitive horsecar lines more attractive. The high labor and other costs of steam operation were proving to be financially ruinous.

By January 1865, several things became clear. The Market Street Railroad despite holding a valuable franchise was financially on-the-ropes. Steam would have to be replaced both for legal (the steam permit on Market Street had about two years left) and economic reasons. In addition, the City was reconstructing street grades to the "official grades." A main reason for selecting steam had been the grades were too severe for horsecar service. Steam was in its twilight. The road, to survive, had to be upgraded.

Extensions would be required to enhance passenger revenue. Management’s last act before foreclosure was on January 30. The main line was extended from the "Willows" (17th Street) to the 25th & Valencia depot of the SF & SJ. Passengers now could ride (with a transfer) from San Jose into downtown San Francisco totally behind steam.

The inevitable came a month later, February 27, 1865. The financial strain was too much for the line’s lenders, the banking house Pioche & Bayerque. Foreclosure proceedings were brought by the banking firm. As a result the Market Street Railroad gained new ownership. Levi Parsons and LL Robinson of the San Francisco & San Jose Railroad purchased line at the foreclosure sale. Parsons and Robinson had ties with then building Central Pacific Railroad, through their joint interest in the Sacramento Valley Railroad. Frank McCoppin was kept in charge as superintendent. By October, SF & SJ had formally absorbed the Market Street Railroad. The operations of the Market Street Railroad were kept separate , however, from its new parent.

In a further attempt to reduce losses, service was curtailed on August 1 to one train per hour. The new owner rapidly decided to standardize the Market Street Railroad with the SF & SJ. Additionally, management was anticipating the conversion to horsecar. The entire system would be converted to a double track standard gauge (4' 8½") operation. However in the short run, the Market and Valencia track would be dual gauge, to accommodate both standard gauge and 5'6" equipment. On February 8, 1866, construction began on the new dual gauge double track alignment. Standard gauge steam trains began running on Market and Valencia Streets on June 8, 1866. The company converted directly the Hayes Valley branch to a standard gauge horsecar line running from Market and Hayes to Laguna and Grove. New Stephenson built horsecars were acquired for this service.

The change in ownership combined with the new standard gauge track on Market Street raised concerns that the SF & SJ would try to run its mainline steam trains down Market Street. The cause of these concerns was because, as time progressed, Market Street’s steam locomotives were becoming more unpopular. They were generally regarded as dirty, smoky, cinder throwers that impeded increases in property values. Fears of long SF &SJ freight trains blocking Market Street traffic aided the anti-steam mood. Agitation mounted for the Market Street Railroad to switch to horse power. The Board of Supervisors reacted by passing an ordinance prohibiting steam train operation, after the temporary steam permit expired, on Market Street east of 10th Street. Passage, in 1866, of this ordinance illustrates the strong political and economic pressures against continued steam operation. In reaction to this ordinance the railroad asked the City for permission to haul mule pulled freight cars on Market Street between midnight and 6 A.M. to lower Market Street factories. This was denied. The enemies of steam were taking no chances, despite the fact that the following March the temporary permit to run steam would end.

The two railroads – the Market Street Railroad and the SF & SJ – were connected to each other at Valencia and 25th on September 20, 1866. Four days later, the SF & SJ’s San Francisco depot was moved to the intersection of Market and Valencia Streets, later the site of the Market Street Cable Railway’s main cable power plant and shops. This depot replaced a temporary arrangement between the SF & SJ and the Central Railroad for a station at 6th and Brannan Streets. SF & SJ and later Southern Pacific steam trains would continue to use the Market Street depot until 1872. The steam trains would share trackage on Valencia Street with horsecars!

During December 1866, the Market Street Railroad ordered twenty-three horsecars from the factory of John Stephenson. These cars were large eight window two-horse vehicles. They would serve the company well both as horsecars and many as rebuilt cable cars. To improve ridership, the Hayes Valley horsecar line was extended from Grove and Laguna, via Laguna, McAllister, Fillmore, Golden Gate, and Devisadero Streets to O’Farrell Street, where a small car house and stable was built.

On March 6, 1867, the ride was over. Market Street Railroad’s last steam train ran. The franchise allowing steam had expired. Horsecar service replaced steam the next day. The fare was cut to 10 cents at this time. However, this was not to be the last steam whistle heard on Market Street.

The steam railroad’s roundhouse and yards at 16th & Valencia Streets remained, serving the new horsecar line, until its conversion, in 1883, from horsecar to cable car. At which time the railway leased the buildings and site to a large commercial stable and horse auction business. The buildings were destroyed in 1906.

The Willows was sold for a subdivision in 1868, and Hayes Park and its pavilion was shortly afterwards. Newer resorts like the Cliff House and Woodward’s Gardens were, by now catching the public’s fancy.

Two of the key founders of the Market Street Railroad did not live long after the changeover to horses. On June 28, 1868, Thomas Hayes died, his finances exhausted by his railroad and real estate ventures. On May 2, 1870, F.L.A. Pioche, who suffered from manic depression, took his life, after personal and financial reversals. J.W. Bayerque had died on day of the sale, in 1865, to the SF & SJ.

Frank McCoppin

was a city supervisor at the time he ran the Market Street Railroad.

In 1867, when he became mayor he left the railroad. During his

tenure as mayor, the land for Golden Gate Park was acquired and

construction on the park begun. He later was a state senator,

president of Board of State Harbor Commissioners and Postmaster of San

Francisco. In this capacity, on September 15, 1896, he inaugurated

the Railway Post Office service in San Francisco. He died on May 26,

1897.

|

Market Street

Extension |

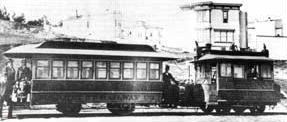

By 1879, plans were being made to extend the Market Street Railway west on Market Street from Valencia through a cut to 17th and Castro Streets. Subsidized by the property owners, by 1880 the necessary street grading was complete. Steam power was, again, selected because the new grades west of Valencia Street were too steep for animal power. An order of six identical Baldwin 0-4-2T steam dummies was placed. Four of these were assigned to the Park & Ocean Railroad (see, "When Steam Ran on The Streets of San Francisco" Live Steam, Nov./Dec. 1999).

The remaining two, assigned Market Street Railway Nos. 1 and 2, starting in 1880 operated on the Market Street extension from Valencia to Castro Street. They had 12" x 16' cylinders with 36" drivers and weighed 40,000 pounds. The passenger cars used were built in the Central Pacific’s Sacramento shops.

During 1884, agitation began to extend the Market Street Cable Railway system from Valencia and Market over the steam dummy route to Castro and then out Castro to 26th Street. After the railway was satisfied that the appropriate grades had been established, construction on the new cable car line began during the winter of 1887-88. On March 27, 1888, steam dummy service was discontinued to complete the cable car line. Two stages substituted until the new cable car line opened on August 27 of that year.

The last Market

Street steam whistle had finally sounded.

Company Rosters

SAN

FRANCISCO MARKET STREET RAILWAY

Steam cars

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 0-2-2T | 16 x 14 | 34" | 15,500 | Albion | 1860 | 24' long; 6' engine, 5' baggage & 13' passenger compartments |

| 2 | 0-4-OT | 9 x 14 | Albion | 1861 | 18' long; 8' engine, 10' baggage | ||

| 3 | 0-4-OT | 9 x 14 | Albion | 1861 | 18' long; 8' engine, 10' baggage | ||

| 4 | 0-2-2T | 9 x 14 | 36" | Albion | 1861 | 24' long; 8' engine, 16' baggage |

Disposition of

steam cars, by number, is unknown. One steam car was sold to the San

Francisco and Oakland Railroad and was on that roster until August 1870

when that company was consolidated with the Central Pacific. The

engine after 1874 was used as a stationary engine in the Central Pacific

shops in Sacramento. Another was reported to have been used as a

hoisting engine in the construction of the San Fernando tunnel. The

passenger cars were sold to the Bayview & Potrero (horsecar) Railroad.

MARKET

STREET RAILWAY– MARKET STREET EXTENSION

Steam Dummies

| No. | Type | Cyl. | Dr. | Weight | Builder | Date | C/N |

| 1 | 0-4-OT | 8 x 16 | 36" | 40,000 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5004 |

| 2 | 0-4-OT | 8 x 16 | 36" | 40,000 | Baldwin | 1880 | 5009 |

Disposition unknown

Source:

Stanley T. Borden, Western Railroader, 1971 and authors

records.

Published in: Jan/Feb 2001 issue of

Live Steam

Go to Part I (All Aboard to the Water "Playgrounds" of San Francisco)

Go to Part III (All Aboard to the Richmond District, Park and Pleasures)

Go to Part IV (From the Mission District to the Pacific Ocean - "Reaches the Beaches")

Go to SF cable car lines in detail

Home

/What

/How

/Where & When

/Who

/Why

Chronology

/Miscellany

/Links

/Map

/Bibliography

Copyright 2001-2005 by Walter Rice and Emiliano Echeverria. All rights reserved.

Last updated 01-Sep-2005